When we say “edition,” who has this come to mind?

And when we say “related product,” who thinks of this?

If you raised your hand for either of those, you are incorrect. These are two of the most common errors we see in metadata today and it’s completely understandable why there would be confusion. In the physical world, edition tends to invoke images of a valuable collectable, while related product calls to mind the bonus item packaged with a book. But when you’re speaking ONIX (and remember when you’re speaking ONIX you’re referring to an individual identifier), Edition refers to the content while Related Product indicates relationships.

Edition = ISBN’s content

Related Product = ISBN’s relationship(s) with other ISBN(s)

Defining the terms this way might make you feel weird initially, but eventually the logic will seep through and then you’ll wonder how you ever used them differently. (Or in some cases never at all.)

Remember that ONIX operates on an ISBN-level, so clean, correct ONIX is a reflection of the decisions already made in the editorial process (i.e., Does this book warrant a new ISBN?) with a bit of marketing thrown in. You want to truthfully describe the book (e.g., “it’s a paperback”) AND highlight what makes it stand out in the market (e.g., “now with 20% new content!”). The rest is just filling in the right composite the correct way, and that’s what we’re here to help with.

Edition

Think of your book as a product, like this Batman action figure:

But then one day, you start only producing this version:

While both of these figures are technically Batman, they're not identical. If you’re advertising “An authentic, beloved Batman” with the first action figure but you send the Batman in the second picture, you’re probably going to have some confused and/or sad customers. Or worse, angry retailers.

Retailers need to know what they’re getting. Which is why a different ISBN is the most effective method of conveying: “Hey, this book is a bit different, take heed.” But it needs to be accompanied by a description of what makes this book different from the last one. Adding collateral, such as notations, critical essays, footnotes, etc. to a work means you're offering something new that other versions of your book lack. But if you don’t state in your ONIX what exactly is new and exciting about this ISBN, why would a retailer, let alone a consumer, pay the extra amount? Or order new copies while others still exist? They’ll only act if they know what they’re getting and know that what they’re getting is what they want.

Accessibility

This may be an edge case for most publishers, but editions that are created for specific audiences (to make the content accessible to more people), such as large print or translations, are considered separate editions of your book because the content is different. They could have a simultaneous release (for example, a hardcover and a large print edition publishing on the same date) but they’re different editions: they have unique ISBNs and offer distinct contextual differences. Libraries especially need this information to best serve their populations. This should be communicated through the Edition code, not in the title or the subtitle.

Common errors

We’ve seen books meant for different markets marked as a previous edition in ONIX — even if they share the same pub date. This isn't accurate. The books are related, but they’re not different editions and their connection should be communicated in Related Product.

Formats are not different editions per se, because whichever format a reader chooses, they’re getting the same content.

Does this mean each format should have the same ISBN? No! Since a number of factors are affected by the format of a book (price for instance) each format of your book (e.g., ebook and paperback) needs a unique ISBN. Think of it this way: If a retailer looked up your book in their system and each format had the same ISBN… well, we’re not saying their computer would blow up, but the incongruity in Carton Qty might cause a rip in the fabric of space and time.

Best practice: If you’re talking about the same format and a 20% difference in content, look to Edition. If you’re talking about different formats, with less than 20% contextual changes, use Related Product.

Edition metadata

A couple of notes about Edition tags: The differences between ONIX 2.1 and ONIX 3.0 are minimal, so the options below, while pulled from ONIX 3.0, could be replicated in ONIX 2.1. (For CataList use, ONIX 2.1 populates the Edition field.)

The tags: Block 1, P.9 Edition

Related Product

If Edition describes a single ISBN, how do we talk about related products?

Take something like this:

This is the same book from the same publisher, albeit in different formats (hardcover and paperback) and with different designs (one for each Hogwarts house). Yes, they all have unique ISBNs, but what if a library or retailer only knows about the Slytherin version so that’s all they order? And if you’re thinking, “Well, what does it matter if someone only offers the Slytherin version instead of the Hufflepuff? It’s exactly the same on the inside.” You try looking a little Hufflepuff in the eye — on their birthday — and tell them that all you have is a Slytherin copy.

This type of marketing is rare though. You don’t normally see four versions of hardcovers AND paperbacks all on the market at once. None of this is intuitive, so you must guide your data end users to your available content or else miss sales. Choice matters to customers. Being able to click through to a mass market paperback instead of a hardcover (or Ravenclaw instead of Gryffindor) version may be the difference that makes the sale.

Common errors

The main mistake we see when it comes to Related Product is that we never see it. EDItEUR marks P22 Related Works and P23 Related Product as optional, but we think that if your hardcover book has a paperback sibling, or a movie tie-in cousin, you should connect them. And, we know, it’s a pain when those versions are no longer active in the market and you have to remove them, but 'tis better to have linked and lost than never to have linked at all.

Fun side note: This is why the terms “Mandatory” and “Best Practices” are in use. Making Related Product mandatory would cause issues in cases where there’s no information to convey, so the best practice should be asking yourself “Do I have data for this composite?” If no, don’t include anything, if yes, INCLUDE IT!

Comparable titles

But wait! Related Product can do more than share format information. What about books that are like your book but are not actually your book? Readers are often seeking similar experiences to the one they just enjoyed. They may want similar themes, writing styles, time periods, etc., and by highlighting these types of connections in your ONIX, retailers' recommendation algorithms are more likely to pick them up.

There's a common pitfall here that we’d like to warn you against: Just because the book is popular, does not mean it's at all like your forthcoming book. A novel about a young boy discovering his love of taxidermy is not a great chaser to The Hate U Give and will probably either be ignored or elicit negative feedback. But someone who just finished The Taxidermist’s Daughter might be interested in another novel featuring dead, stuffed animals. (And yes, there's a taxidermy shelf on Goodreads.)

Here’s the second pitfall: If someone has just finished a book and is looking for comparable titles, the last book they want to be recommended is the same book they just finished.

If your book has a new ISBN (i.e., a new edition or format), it's not a “Similar Product” to its previous ISBN, it’s an “Alternative Format.” When we check the official EDItEUR Product Relation code (list 51, code 23), we find that Similar Product refers to “another product that is suggested as similar to the product.” It’s a reference guide, not a format identifier.

We understand. You want customers to know that there’s another format out there and to give them choice, but when you use Similar Product for a new edition or format of your book, what you’re telling retailers is: “My book is like this book so you should sell it in a similar fashion,” which is kind of a logic black hole. Remember, all data provided should be actionable. Readers are less likely to choose your book when their reference point is kind of useless. It’s like saying: “If you like Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire then you’ll love Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire: Ravenclaw Edition. We mean, true, but not helpful. Never use Similar Product on the same title. It's not similar, it is the same — even if it's a different edition.

Related Product metadata

ONIX 2.1 and 3.0 are fairly close when it comes to filling out Related Product. Most of what was available in 2.1 has been deprecated, primarily because 3.0 asks for so little in comparison (List 51 pretty much covers it). The following examples are 3.0, but are easily replicated in 2.1 (and please note that only 2.1 is currently used for CataList).

The tags

P.23 Related Products

<RelatedProduct>

<ProductRelationCode>List 51

<ProductIdentifier>

<ProductIDType>List 5

<IDValue>ISBN of the other title

We’ve heard time and time again that because some systems don’t support these data points, it seems pointless to bother or to change what is currently being done. But by not supplying this information or supplying portions incorrectly, you eliminate any chance of useful information making it to the right person at the right time. These composites exist because the more information you supply, the better your chances of boosting discoverability and avoiding lost sales.

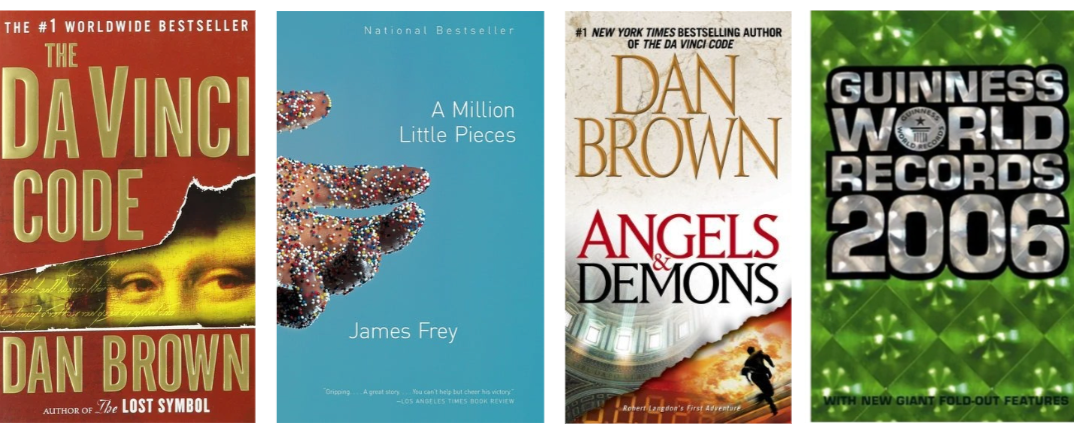

The most popular books in Canadian libraries in 2025.