When three similar (and difficult) questions came in to the BookNet offices recently, we thought it might be time for a blog post: an overview statement that might help to show the value of doing metadata.

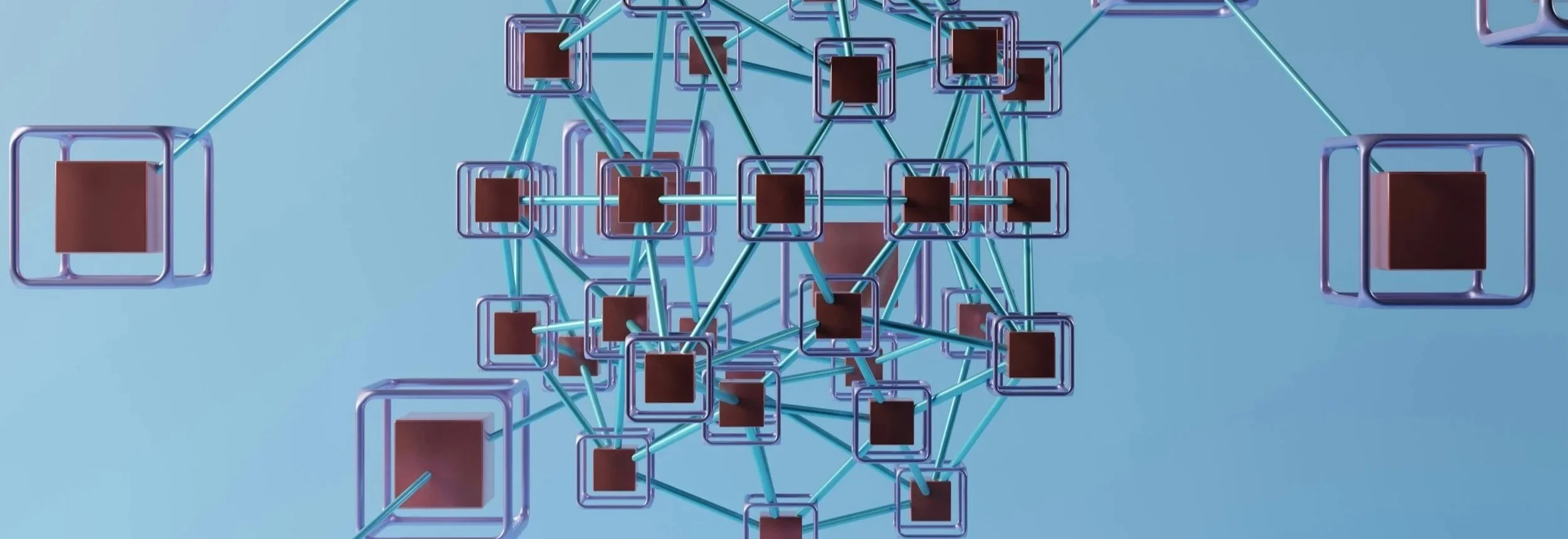

Book metadata (i.e., information about books) doesn't mean anything until it's traded

It's the hand-off, internal or external, that defines book metadata's existence or function. Metadata is provided to someone else for a purpose — otherwise you don't need it.

Books have always needed metadata — even before Gutenberg, bibliographies were a necessity — and its study is the foundation of more than one academic discipline. A book's content always needs to be described because it's complex, possibly unique, and hidden between covers.

Metadata used internally within a company tracks the product's creation and workflow, business terms, and costs. It defines current metrics and the metadata forms part of the corporate history. The metadata supplied to other companies is also used internally as it comes back in reports from partners.

External metadata is provided to fill another company's dataset, start a process, or provide an update. It charts a route for money's return and it supports discovery for those titles.

All mass-produced books are digital products

A print book is just a digital file in a physical format.

There's a weird contradiction: The metadata on physical books embodies more reality than digital metadata. All books are tracked using metadata but the abstract digital product depends on equally abstract digital metadata while trading partners help verify physical product records. If a warehouse has a box and no data, or a retailer scans an ISBN and can't get a price, they let someone at the publishing house know. They might even get charged a fee for the mistake. Digital products, on the other hand, can just disappear and the primary responsibility for accuracy remains with the product creator. Digital books might not be available for sale because the file and record don't match. That can mean either the file wasn't sent because the digital distributor didn't load it, or did but sent it as-is so it wasn't found, or it was found without instruction so it was shunted aside to await them.

The primary purpose of "external" metadata is to directly support sales

Mostly a publisher is loading information to a retailer's database. That data should provide all their business information (price and terms) as well as all the information that they need to display so that a consumer can make a buying decision.

But a secondary purpose of metadata is to indirectly support sales by promoting discovery. Discovery can be between businesses or by consumers.

A publisher's internal metadata describing their business needs provides their external partners with the basis to work with their books

This is a hard one — as it's not like a P&L (profit-and-loss statement) is made public, so not all internal tracking needs are part of external metadata — but neither a publisher's business nor their partners' can function without knowing what a book is about or who the author is. A publisher sets the terms, the costs. Their partners' hopes for their return (a.k.a., planning) are defined by what publishers tell them.

Effective book metadata supports business needs and if publishers aren't using their internal resources to create external metadata then they're not being efficient. It can be done but the higher the volume the more financial drag is created. What publishers track to succeed and what others need to know correspond in too many ways not to maximize use of internal tracking.

History affects sales

Stick with me on this one as the credulity tightrope gets taut, but you probably agree that a "good book" has enduring value. We know them when we read them. That value must be real because they make both authors and companies. Their cachet lasts long after their profits run down. Good books provide social status and a basis for tenure. Readership, focused or widespread, ultimately decides what's good but metadata supports a book's social capital and maximizes its benefit — it's part of the historical record. Generating such capital isn't an ROI sort of thing but I'd say that a book worth publishing is worth describing well enough to fully support its social capital. Doing anything less at the start shows that you don't believe in the bet you're making.

Let's spare a moment's thought to consider whether a digital book carries less social capital. I've already suggested above that digital products can disappear because of problems in metadata. When you withdraw a digital book from sale it's as if it never existed, while a print book continues in the used book market.

Supporting discovery through metadata is more important now than before. A print book can be found because it's left lying around in a bookstore or Emma Watson is hiding them on the subway again. In the days of print-only books, this was how books were found. Stores and libraries were where you found books and placing them there was a major portion of what publishers did.

A digital book can only be found by metadata-supported discovery tools. (A print-on-demand title is the same as an ebook for our purposes.)

We want books to be found on their own merit because good books should be and we're romantics about the value of them. But there's no discovery to be had without metadata today, so we should apply our romantic aspirations for the book there.

That's why we do metadata: We want books to be found.

Our forced reliance on metadata is because we can no longer rely on anyone coming to look for books in a "place."

Except that we can: Libraries remain an important part of book discovery and part of a book's social capital. They embody social choice, the historical record, and independently track use and even their digital display works independently for discovery. Both publishers and bookstores benefit from libraries. And, yes, of course bookstores are important and they drive discovery as well, but they're limited to books that can predictably sell. There's an apparent perception, maybe more media than true, that publishers see libraries as competition for sales. As well, tight resources make publishers reluctant to invest in the continual upgrading of metadata. I think both are detrimental to the longterm maintenance of the industry's reader base.

A conversation with Greystone Books about changing distribution as an independent publisher.