If the results of our consumer study, The Canadian Book Buyer 2015, are any indication, consumers only sometimes know what they're reading. Specifically, whether when the book they're reading is considered to be a juvenile fiction title as opposed to an adult fiction title. That's where things seem to get murky for the general reader.

First, a little background about our survey: We asked 4,277 people whether they had purchased a book in the past month, regardless of format (print books, ebooks, and audiobooks all counted) and 19% of them said yes. We then asked these 784 people more questions about their purchases (you can see the whole report with all of the insights from their answers here). Side note, this 19% of survey respondents who were book buyers were big book buyers—they purchased an average of 2.8 books per buyer per month!

To get back to our original question, we were interested in what types of books the respondents were reading so we asked them to provide the ISBNs of the books they'd purchased, where available, as well as who they thought the audience was for the book, i.e., was it an adult or juvenile book? The results were quite interesting.

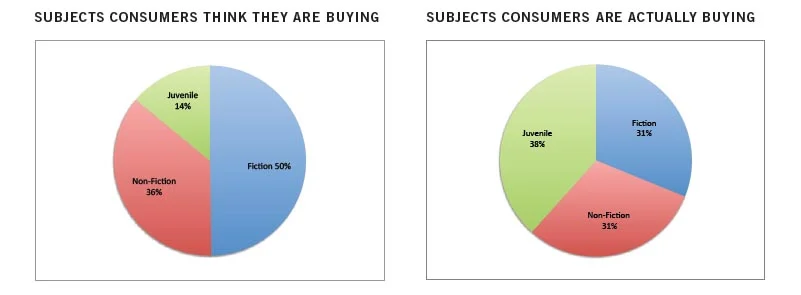

Consumers categorized 50% of their book purchases as fiction and only 14% as juvenile. However, when we looked at the ISBNs we found that actually only 31% of the books were considered fiction and 38% were juvenile. That's twice as much juvenile fiction being bought than consumers originally thought.

Are adults buying juvenile titles and not realizing it? Earlier this year, we asked some industry experts to give us their insight on what might be happening here. Rachel Letofsky, associate agent at The Cooke Agency, believes "that adults are increasingly reading YA because YA is increasingly becoming more and more diverse and complex and dark." She wonders if genre readers might account for some of the misidentification of YA fiction as adult fiction.

"[YA is] being divided into subgenres, which is why it's storming the market, and so people who like reading in those subgenres, like a fantasy reader, can easily access YA fantasy and may not feel like they're reading YA per se because they are attracted it for the fantasy aspects of that genre."

Léonicka Valcius, product manager and digital marketing coordinator at Scholastic Book Fairs, has another take. "I'm wondering," she says, "if this might be a discrepancy between what industry category titles are and what consumer, mass popular, internalized labels are." For example, "a book that is a YA thriller with teenagers in a cabin being attacked or something, might not count as juvenile to someone if you're thinking juvenile as 'for little kids,' but it is certainly fiction. So I think it makes sense for a customer to label that as fiction if the question is 'Which of the following categories best describes this book?'"

Perhaps the industry does rely more on labels than the general consumer, but does marketing and merchandising play a role as well? Allister Thompson, editorial director of Fierce Ink Books, thinks this might be the source of some confusion. "The way we're marketing YA now is a lot different to 20 years ago—the covers look like adult books. And the way that you're buying the books has changed as well. You may be buying off Amazon and not looking at the metadata to see what category it's in. You might walk into Chapters and it's piled up on a table at the entrance. You don't know what kind of book you're reading; you just know that you're going to try it out."

During our discussion, Rachel also mentions "Against YA", a Slate article from June 2014. The subtitle of the article sums up nicely the argument of its author: "Read whatever you want. But you should feel embarrassed when what you’re reading was written for children." It's possible that this stigma is widespread and perhaps survey respondents didn't want to identify as people who read YA because of it.

The three industry experts had more to say on this topic. For the full discussion, listen to our podcast episode, More adults are buying YA books for their own reading enjoyment, but do they realize it's YA?

It's been almost a year since Young Adult titles have had their own BISAC codes. It's hard to know whether this will help to clear up some consumer confusion, but perhaps decoupling YA and the juvenile categories will help align industry classifications to informal consumer labels. It will be interesting to see the next survey results.